Creator of dust, cosmic cleaning lady

Rest on the seventh day? By then, everything’s already covered in dust.

The Portuguese poet Adília Lopes passed away on December 30. Only then did I learn that people had criticized her as a “trendy” poet or something along those lines. In general, that doesn’t matter. In many specific respects, however, it does, and it mattered to me because the critiques I found were quite stupid. Nobody has to like anything, of course; what bothers me is seeing how so many judgments are made based on so little. Sensitivity and perception are mediations, ways of encountering; it’s a pity that they’re taken as givens, and that from this comfortable self-assurance we set about judging. But that’s not what I want to talk about.

Adília has been very important to me, and in our encounter I have never perceived or received her as even remotely simplistic. I find her immense, abysmal. And I think I can at least articulate one aspect of her infinity, one that visits me daily.

As soon as I wake up, the three cats who live with me come running to greet me and call me to the kitchen; even though they have food available all day, we’ve established a breakfast ritual. I decorate small plates, sized just for them, with a lovely arrangement of wet food, various biscuits, and the famous churu - well known to anyone familiar with cats. There are many videos online of people preparing meals for their cats in special bowls and dishes with the utmost care. In the end, both parties delight: the human with the feline, and the feline with the banquet. I, too, enjoy seeing how they undo the arrangement by devouring it. While they eat and play, I wash the dishes, clean the litter boxes, sweep or vacuum the floor, wipe it down, boil water for coffee, put out fresh water for them, and so on. Only when I’ve finished all that do I sit down, cup full and computer on, to check the news and start working. It takes time. As soon as I clean the litter boxes, the kitties run over to use them, so I clean them again. I wipe the floor before setting out their dishes, and after they eat, I wipe it again so that no scraps remain - an invitation for other diners. During this ritual, we chat. I often say that I’m “de-entropizing” the house. I learned this expression from Adília. I also remember something my dear grandmother Nancy told me about her mother. My great-grandmother Appolonia (whom I used to call Grandma Polônia, the Portuguese word for “Poland”, haha) used to say that a housewife’s work was the work of a madwoman, something done only to be undone: you tidy so that it can be untidied, you wash so it can be dirtied again, and so on. It’s a daily fight against entropy.

God, Adília Lopes tells us, is our cleaning lady (“mulher-a-dias”), offering us anti-entropic gifts (life, faith) that we disdainfully throw away. The poet, she writes elsewhere, is also a cleaning lady who arranges puzzle-poems on a table placed in a dog’s path. When the dog passes by, “the table falls” / “and the puzzle remains unfinished / on the floor.” Adília’s cleaning lady and Adília-as-cleaning-lady are an anti-entropic force. I wish I had told this to my great-grandmother, whom I only knew as an elderly woman, always seated in a dark armchair, her skin very white, her hair exceptionally white, a whiteness interrupted only by the gleam of small blue eyes behind glasses. By then, she was constantly knitting or crocheting. That’s the image I hold of her: a nearly ghostly woman, so pale, weaving and unweaving threads. I wish I had told her that her madness, our madness, this daily tidying only to be untidied, cleaning only to be dirtied, is a way of postponing the end of the world. That this madness is negentropic.

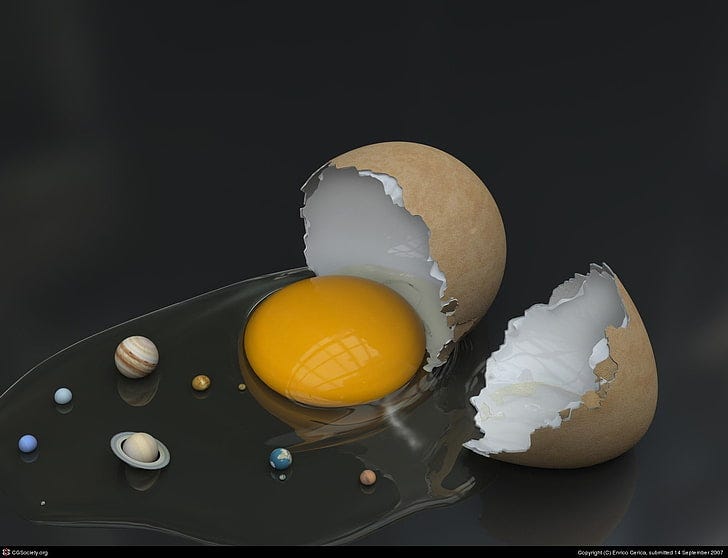

A few years ago, I read for the first time Pamela Zoline’s masterpiece, “The Heat Death of the Universe". This short story, published in 1967, is composed of alternating sections: a very ordinary housewife’s daily life and the second law of thermodynamics. It culminates with the woman throwing eggs across the kitchen in revolt. She precipitates entropy, accelerates it, exhausted by the negentropic work she did not enjoy, exhausted by the very world her work sustained. Gaining time for what, for whom? Certainly not for herself, in the case of a 1960s housewife. The eggs spinning in orbit are planets that explode on impact with the floor. I think of that as I de-entropize the house each day, and think about the people, both human and non-human, the relationships and things and worlds whose end I insist on delaying.

Adília Lopes wrote, in a poem-conversation with a 16th-century Borgia saint and the poet Sophia de Mello, that “life has to do / with filth / with entropy.” She also warned us of the danger of purity in her famous “Anti-nazi”: “Cleanliness / can be / worse / than filth // Order / can be / the greatest / disorder.”

I borrowed a line from her “Louvor do lixo” [In Praise of Garbage] for the title of an article: “uma pomba pode visitar o lixo” (“a dove may visit the garbage”). In that poem, the sacred cleaning is offered to an entropic goddess, to whom the poet prays: “nos dai hoje / o pó e o amor” (“give us this day / the dust and the love”). In contrast to the saint who, upon seeing a decomposing female corpse, swore never again to love or serve a god who could die, Adília prays in the temple of a capable god: “mas é preciso agradecer o pó / o pó que torna o livro / ilegível como o tigre” (“but we must give thanks for the dust / the dust that makes the book / as illegible as the tiger”). Love and dust that, burning bright, answer yes to William Blake’s question “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

That’s enough for today. I’m not going to throw eggs, because eggs are precious to those who made them: hens that, whether confined to battery cages or free to stand on the ground, remain forever under the sky, even if they’re not allowed to watch it. Gift and theft, life and death. Only those who have died can be resurrected.