Francis, the Sun and Kinship

Surrounded by the pain of a multitude whose bodies power debases and degrades with an unspeakable fury, I offer a creaturely canticle of praise in multiple voices.

I learned the other day that The Canticle of the Creatures is the oldest known poetic text in Italian literature with a known author. Perhaps I should have already known this, given that during my master’s, I studied a bit of Provençal poetry, Dante, Leopardi, and Primo Levi. Who knows, maybe I did know once and then forgot - like Deleuze, who perhaps lied when he said it, I do not store knowledge in reserve. So, I rushed to the original text, from which I now return with news and an invitation: for you to join me on a small solar-powered journey through the cosmic making of kinship.

Much has been written about Francis' influence on Dante, who dedicated Canto XI of Paradiso in the Divine Comedy to him. There, we read that "a Sun was born into the world" [nacque al mondo un Sole], a verse that imbues the poet-saint’s origin and nature with a mystical-earthly flavor. This association with the Sun was quite common in Franciscan sources; Bernard of Besse, for example, in the mid-thirteenth century, opened his Book of Praises thus: "Like a rising Sun, the blessed Francis illuminated the world with his life, teachings, and miracles" [Quasi sol oriens mundo beatus Franciscus vita, doctrina et miraculis claruit]. In Paradiso, written in the first decade of the fourteenth century, Dante abandons the quasi, which in Latin means "as if" or "almost" (which, incidentally, enriches the understanding of "almost-event" in Viveiros de Castro), and simply says "a Sun." And he goes further: exploiting the similarity between the name of the city Assisi and the word ascesi - to ascend, though at that time not in a religious sense - he adds: "whoever speaks of this place / Should not say Assisi, for that would say too little, / But Orient, if they wish to speak truly" [chi d'esse loco fa parole, / Non dica Ascesi, chè direbbe corto, / Ma Oriente, se proprio dir vuole]. Thus, Francis becomes Saint Francis of the Orient, an ever-rising Sun in an eternal dawn never fully completed.

Let me add a note to explain myself: if I love Francis, it is because I share his love for the material world, for all things —each different, all of them creatures. As my dear Rondinelly said, in Francis we find "the Gospel renewed, as good news: the Kingdom of God belongs to the Earth." I will not discuss the broader context or historical figure here - beyond lacking the expertise, there is already a wealth of material on the subject.

I begin, then, with my personal connection, which, like that of many Brazilians, is linked to animals. Although I was baptized in the Catholic Church, I did not grow up in a Christian family and didn’t really know who God and Jesus were until I went to school. When I asked my mother to let me attend catechism - all the girls did, and the church was only a few blocks from home - she simply said: no. At the time, the curriculum still included the subject of Moral and Civic Education, conceived during the dictatorship. Around the sixth grade, one of the textbook lessons covered "religion" - Christianity, of course. It began directly with the argument from design, the famous watch from which one must infer that there is a watchmaker. Very curiously (or not), both in the book and in class, the choice of the watch among all things in existence remained unexplained; no one speculated on why organisms were compared to machines, much less why we so readily accepted the comparison. Anyway, following the argument from design were three questions: i. who are we, ii. where do we come from, and iii. where are we going? The answers, simple and direct, were: i. creatures of God, ii. from God, and iii. we shall return to Him. I went back to my mother and asked her what that was all about. She said it was nonsense and that I should memorize it, answer it on the test, and forget it.

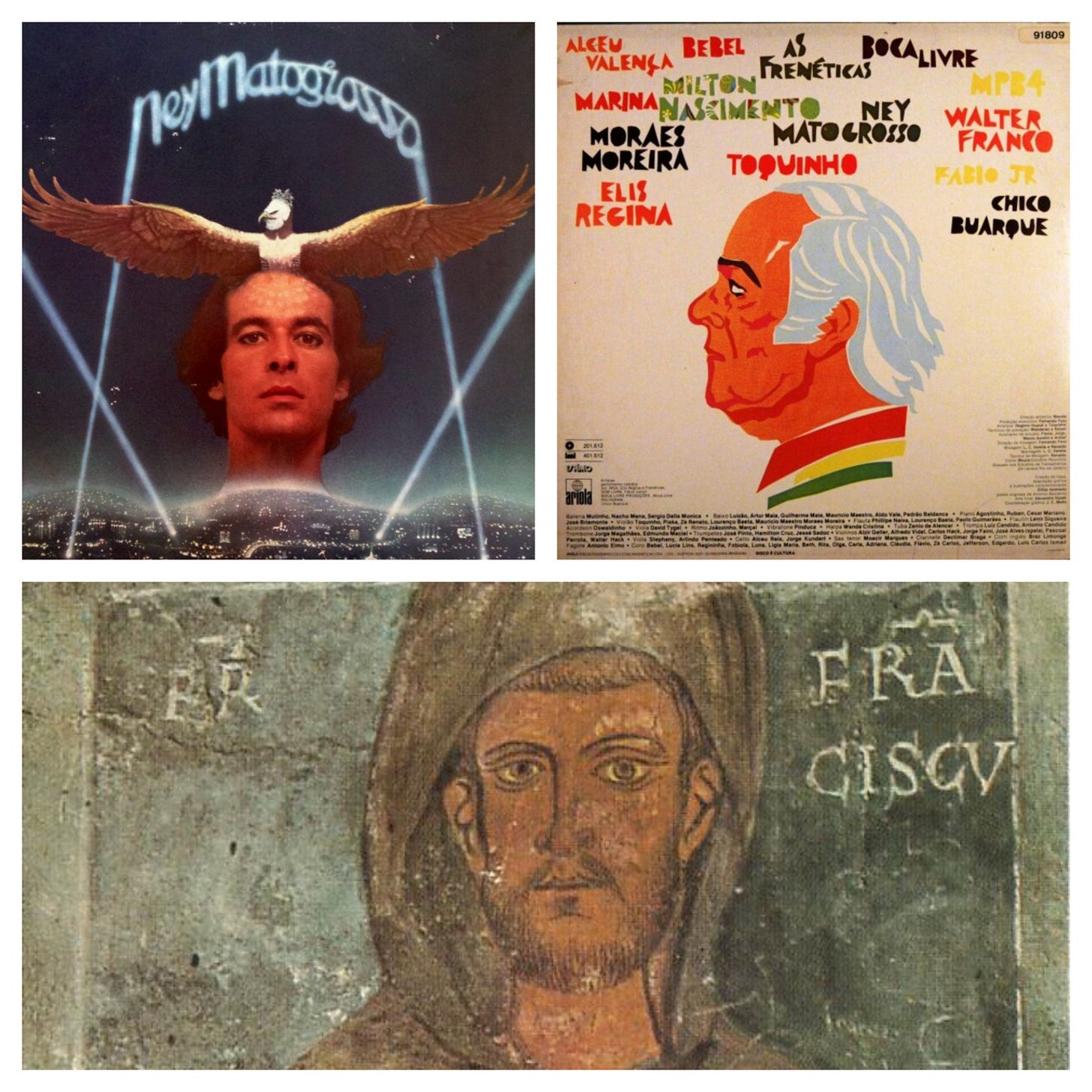

The only thing I knew about Saint Francis at that time came from the song interpreted by Ney Matogrosso in Arca de Noé. I was a fan of Ney — my first LP was his 1981 album, whose mesmerizing cover showed the artist’s head merging with an eagle. In my head, however, it was Vinicius de Moraes’ drawing on the cover of Noah’s Ark and Ney’s voice that fused with the idea of Francis.

As an adult, at 22 and living with my boyfriend, I brought home a kitten to live with us - my love for cats, too, I learned from my mother. Baby Berenice, who came from SUIPA, was sick and lived only five days. A few weeks later, Eleonora arrived, also a kitten, also sick. I turned to everything I could, from modern sciences to pacts with the more-than-human world. Nora lived — for many years, actually — and with her recovery, she made me donate to animal shelters and distribute a thousand of Saint Francis prayer cards. Since then, I have kept his image in my home.

Only much later did I become enchanted, through study, by the stories of this revolutionary figure who confronted a Church of extreme violence and, for a moment, made it bow to him. A contemporary of the Crusades, which claimed millions of lives within and beyond Europe, Francis proposed respect for Muslims and peace agreements. The son of a merchant, he chose poverty and lived as a poor man among the poor, criticizing property and accumulation. He saw women as spiritual companions; Clare, who is as great as he is, he considered his equal.

For Francis, the material world, full of feminine and other-than-human bodies, was neither temptation nor corruption but a divine image. He greeted birds, returned fish to the river, gave wine to bees in winter. And he spoke with wolves. It is said that in Gubbio, a wolf was terrorizing the town, and instead of exterminating him, Francis made a pact with him. Far from being a moral fable about taming the beast, the story holds something more radical: a contract of cohabitation, a multispecies understanding. He loved the creatures of this world, here, on Earth, because he considered them all of Heaven.

I like to playfully call him a pagan saint. I care little for arguments over fidelity: to me, Francis is an animist saint of a world entirely alive.

In 1228, Thomas of Celano, already writing in hagiographic form — that is, in a literary genre sanctioned by the Church but still before the great domesticating rewrite that Francis’ life would undergo - recounted that:

When he encountered an abundance of flowers, he would announce the gospel to them and invite them to praise the Lord, as if they possessed reason. Likewise, he would address the fields of grain and the vineyards, the stones and the forests, all the beautiful things of the fields, the waters of the springs, even the greenery of gardens, the earth and the fire, the air and the wind [...] In short, he called all creatures by a fraternal name and, in an exceptional way unknown to others, discerned the hidden things of creatures with the acuteness of his heart. (de Celano 1228: 1.29,81).

A sun, brother to another sun - and to everything else. Faced with this human who spoke with animals, fulfilling Lévi-Strauss’s most intimate desire, I finally turn to the canticle.

The poet Guilherme Gontijo Flores dedicated his translation, which I drew upon in the Portuguese version of this text, to the birth of his second child in 2014. A decade later, I echo his invocation, still so timely, and ask for permission:

I will not reproduce the poem here, as its verses are well known, and I do not intend to analyze it in depth or detail. I like to think that its force and persistence reveal an atavistic memory we carry in our bodies of the infinite connection and connectivity not only of life but of the universe (or rather, the pluriverse) in kinship.

Francis’ process of fabricating kinship is also connective: the Sun, which in Plato’s Republic is described as the “offspring of goodness,” “child of good things” [ἔκγονός τε τοῦ ἀγαθοῦ], becomes in the Canticle a kind of “face” or image of God [de te, Altissimo, porta significatione], of whom we are all siblings. The Earth, in turn, is made kin in two ways - both as sister and as mother. Or did the saint create a different kind of relative, a sister-mother? The verses “Our Sister Mother Earth / who sustains and governs us” [sora nostra madre terra / la quale ne sustenta et governa] brought to mind Tellus Mater, the Roman deity who was in Rome before Terra and coexisted with her in an imperfect fusion.

I have been deeply interested in Tellus ever since I encountered the Ueinzz Theater Company at the invitation of filmmaker Mariana Lacerda, who was filming a documentary about the group and the making of their play Telúrica. It was in Ueinzz that the idea of Pax Telluris, the telluric peace, was born as a contrast to pax imperii. But that is another story.

Returning to the land of the rising Sun-Francis, in the Canticle she “sustains us” — and sustain here carries the same sense as in English: to support, to uphold, to endure, to nourish, that is, to provide subsistence. This reminded me that when I first started reading about Tellus, I found in the Leiden etymological dictionary that:

The root could be PIE telh₂-, meaning “to bear, to support,” […] In fact, Sabellic shows a pr. *telne/o- where Latin has tollo 'to bear';(“to uphold, to lift”) [...] Thus, the Earth would have been referred to as “bearer” or “support” (of the sky, or of the creatures and objects on the earth) (2008: 608-609).

In short, Tellus is the one who holds up the sky so it does not fall while simultaneously sustaining the creatures upon her, embracing them so they do not drift away into space. Our Sister Mother Earth, the name of a goddess, leads Francis, in this way, to encounter Davi Kopenawa by Roman paths.

At this point, I was about to weave in references to climate, return to the Sun and its relation to fire, speak of the socio-environmental catastrophe and the links between disaster, catastrophe, astrology, tragedy, and the goats themselves, my dear Faunus (it ought to be Pan, but Aleister Crowley and his gang have sullied the great god). The problem is that, like Leopardi, shipwreck to me is too sweet in this sea. But not yet.

To conclude, then, one last remark: Francis thanks God for “our sister bodily death / from whom no living man can escape” [sora nostra morte corporale / da la quale nullu homo vivente po’ scappare]. Consider this: our rising Sun makes kinship even with bodily death. I dare to interpret: not with the death of death, that insufferable, tiresome absolute end so desired in some quarters, but with bodily death, the agent of metamorphosis, of infinite transformation that connects and disconnects, inventing the new, again and again.

That one cannot escape from it is significant, for this verb, escape, scappare, literally means “to shed one’s cape/cloak,” to elude a pursuer by allowing them to grasp only an empty mantle. If death cannot be escaped, if one cannot simply run away, leaving it clutching only a loose cloak, it is because the body itself is the very garment. A body, clothing, or vestment. Stripped bare, Francis encounters the Kwakiutl (Kwakwaka'wakw):

Animals declare themselves to be people wearing animal clothing (Boas 1895:169). Thus they are kin to mankind generically, as well as specific and totemic founders of lineages. Though linked by a common humanness, animals and humans are apart in their domains and the connections between them are not intended to be self-evident. Mountain goats find it necessary to tell a hunter they are people. Other animals, who habitually remove their animal clothing when at home, are embarrassed to have people come upon them in undress. [...] Their animal existence resides in their removable outer surface, their covering. A mountain goat gives a man his skin with which he can then successfully hunt the species, another version of animals giving themselves to men. And as I observed earlier, animals remove their skins when they seek supernatural power by diving into deep, fresh water[...] (GOLDMAN 1978: 182-183).

With this profanation, I take my leave for now, once again repeating Gontijo:

even surrounded by the pain of the world, there will be — so I say —

there will be space for a canticle.

I quote Rondinelly once more:

It just occurred to me that Francis was the son of wealthy merchants, and that this was the era of an early urban and commercial renaissance, the moment when Christendom was taking its first steps toward capitalism. It was in this context that Francis’ gospel of the earth emerged - as a gentle offering of an alternative path, a path to salvation from within the heart of that culture itself, an offering so melancholic in its impossibility for the emerging classes of the time, because it called for renunciation of that entire path of greed, accumulation, and destruction. Instead of profit, creation; instead of commodities, creatures…

Praised be, my kin, each and every one of you, for the canticles that soothe our skins in moments of pain.

And may we never forget: jaguar is my kin. So is wolf.