Lithium’s Thirst and the Mines of the Mind

To stay sane, we hollow the Earth.

This essay was first presented at CPF-SESC in September 2023, as part of the course Other Lives, Other Bodies – Alliances and Encounters to Build Cosmopolitics and Places of Life, at the invitation of Christine Greiner. I had the honor of speaking right after the brilliant Mel Y. Chen, in a session alongside the equally brilliant Joana Cabral de Oliveira. Later, the text was published in Portuguese by n-1 in the form of a cordel, as part of the Pandemia das Bordas box set.

I would like to thank the amazing Isabela Mota, Ismar Tirelli Neto, and Leonardo Levis for introducing me to the history of the rise and fall of the Poçocaldense Empire - I love you all! And we shall still bring the Mummy Elixir project to life.

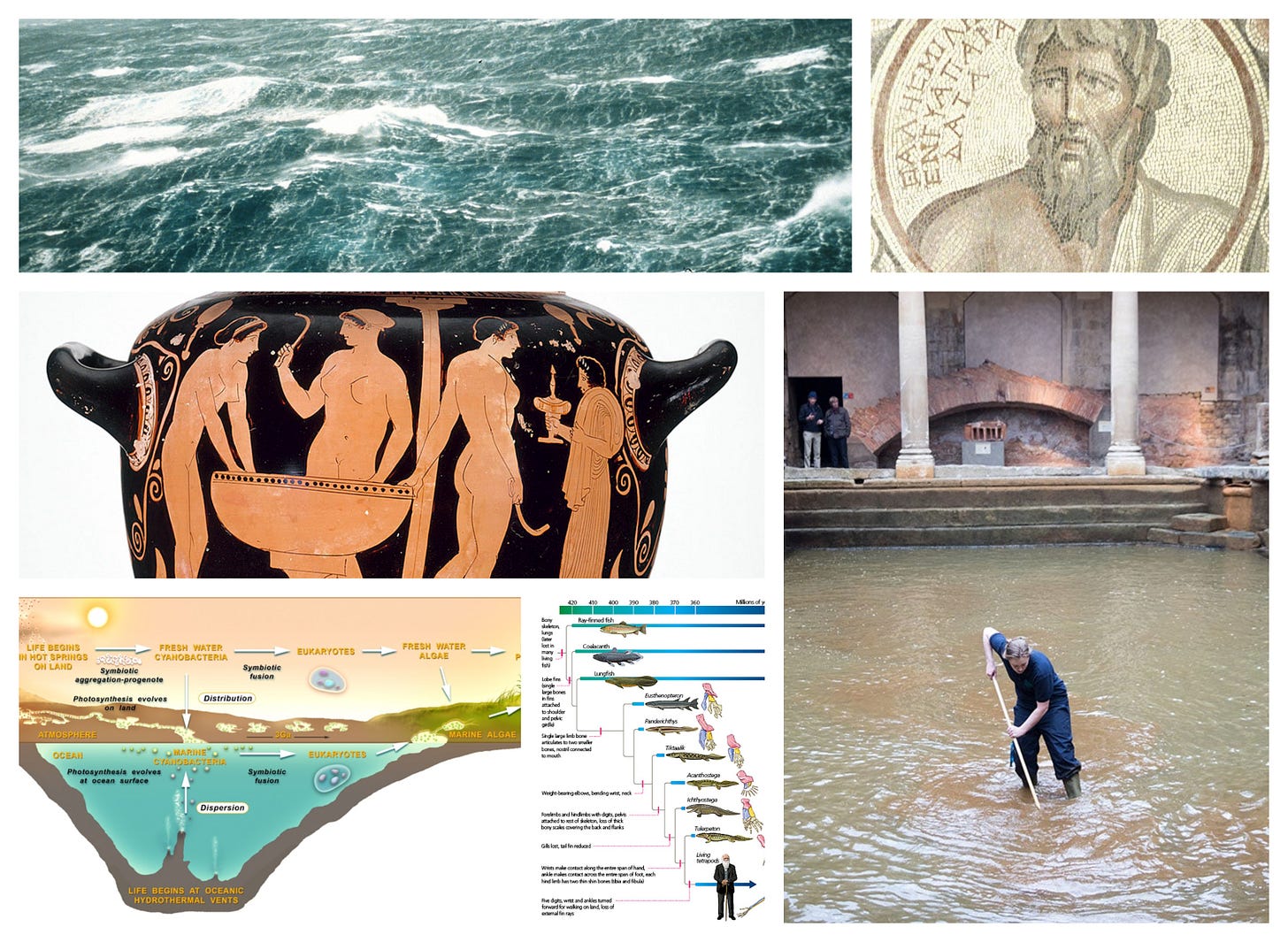

The history of therapeutic baths is long. Healing through immersion may still hold something of the communion of life in water before the events of terrestrialization, between 350 and 400 million years ago. If, in the beginning was water and we were together in it, why not imagine that each time we plunge in, we find ourselves in the midst of life’s irruption?

Single-celled organisms aside, much water has flown under the bridge since then. In late 18th-century Europe, spa models as we know them emerged. With opulent architecture, they spread like a fever - or rather, promised to cure many. There were blazing pilgrimages, mostly by the affluent, but also by factory workers, gathering (at least rhetorically) social classes in pursuit of relief from their afflictions.

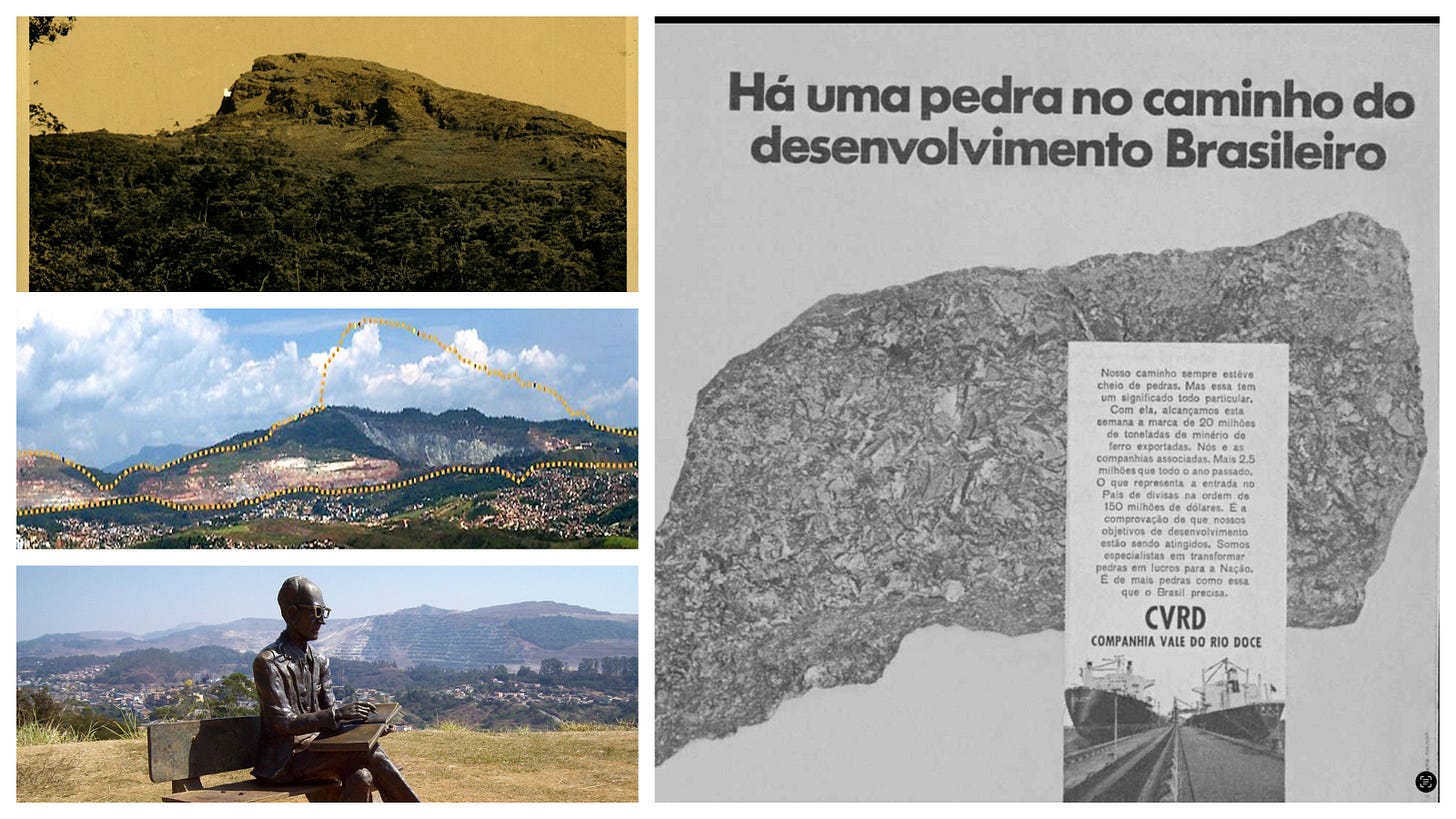

In Brazil, the state of Minas Gerais concentrated the largest number of hydro-medicinal cities. Caxambu, Cambuquira, Araxá, Lambari, São Lourenço, Poços de Caldas, and Baependi, for instance, had the quality of their waters tested and attested to by both medical science and a host of ailing individuals who sought them out to cure “rheumatism, syphilis, dermatitis, cystitis, tuberculosis, pneumonia, chronic wounds, asthma, and hemorrhages.”

One of these cities shone more brightly than the others: Poços de Caldas. At the end of the 18th century, the joyous news arrived: smelling of rotten eggs, a thermal spring was discovered in the region and was said to be effective in treating skin conditions. With the gold rush coming to an end and wildcat miners settling in the area, it did not take long for Poços de Caldas to flourish, becoming a luxury destination and a privileged witness to Brazil’s history and its pains, from the Empire to the Estado Novo. Dom Pedro II wished to dip his feet in its waters, and some fifty years later, Getúlio Vargas maintained a suite at the Palace Hotel, where the Palace Casino operated during the period when gambling was legal in Brazil. Nothing like placing a bet and then purifying oneself with wholesome - or holy - baths. Figures such as Carmen Miranda, Santos Dumont, Olavo Bilac, João do Rio, and Ruy Barbosa also experienced the miraculous waters of Poços de Caldas.

The Palace Hotel still stands, a magnificent building rising majestically - or republicanly, depending on whom or what one wishes to honor -, a kind of monument to a city whose flame was extinguished with the prohibition of games of chance and, by chance or misfortune, with the discovery of antibiotics. Yet, if pills and injections triumphed over those waters - in cahoots with the ban - that does not mean the waters lacked therapeutic qualities. Who’s to say how many they held? I would like to tell a story of therapy and a great deal of water.

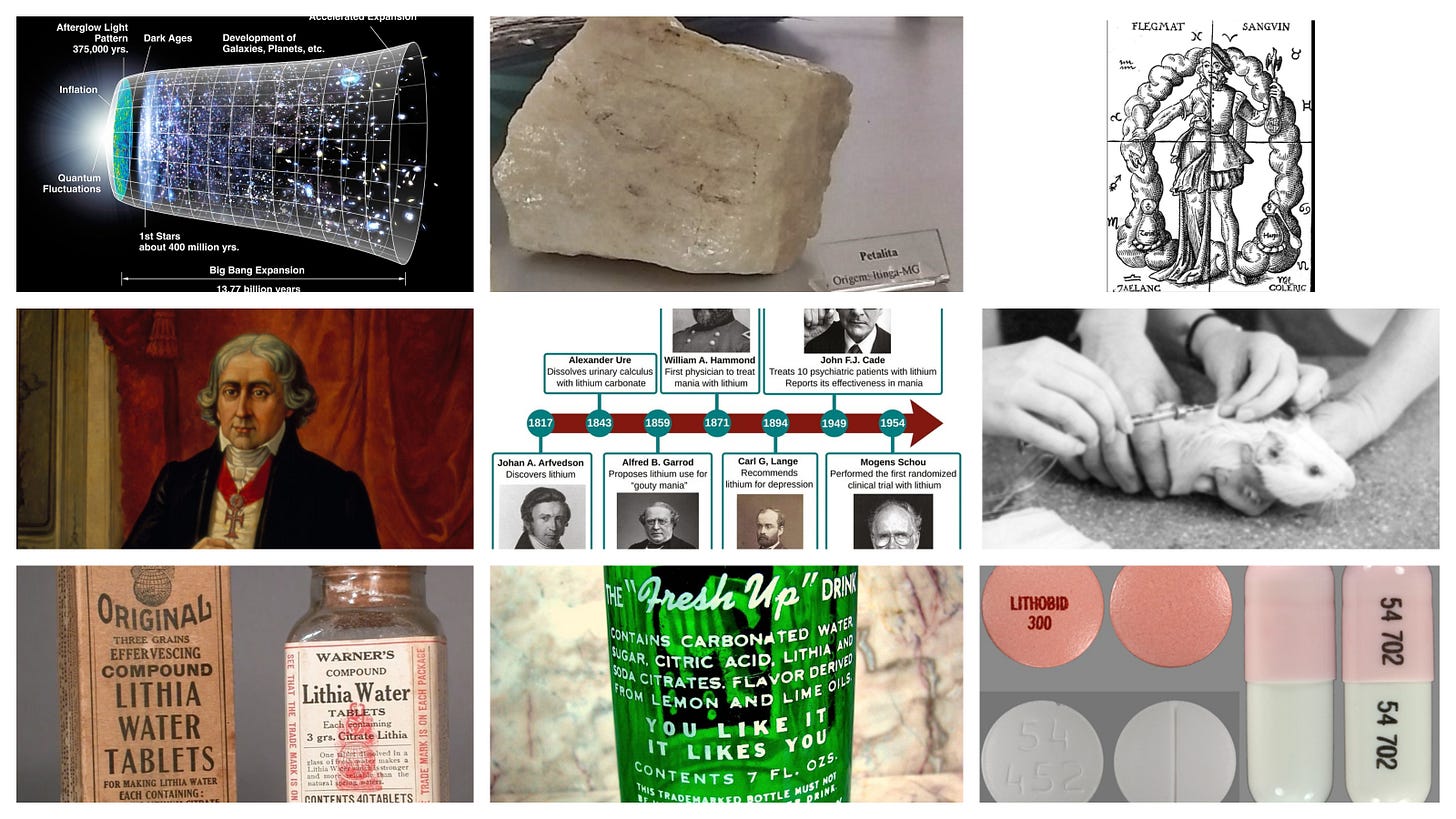

Legend has it that, shortly after the Big Bang, around 14 billion years ago, the universe contained only hydrogen, a bit of helium, and a tiny trace of lithium. Then, in 1800, during an excavation in Üto, a mineral-rich island off the east coast of Stockholm, the patriarch of Brazilian independence, José Bonifácio, discovered the mineral petalite and sent it to the chemist J. A. Arfwedson, who identified within it an element previously unknown: lithium.

In 1843, surgeon Alexander Ure, having successfully dissolved kidney stones in vitro using lithium solutions, attempted to replicate the process in vivo. Not only did he fail, but the patient on whom he relentlessly tested the treatment fell into severe depression and died (the cause was never disclosed). By that time, however, lithium was already being used to treat gout. The prevailing theory suggested that the metabolic dysfunction responsible for gout also contributed to mania and depression, which led to lithium’s use in treating these conditions - as well as epilepsy, diabetes, cancer, insomnia, and more.

By the late 19th century, lithium was being used anecdotally to treat depression and mania. In the United States, cities with lithium-rich water sources flourished as wellness destinations, exporting their alkaline waters. Until 1950, the soft drink 7 Up listed its ingredients right on the bottle: carbonated water, sugar, citric acid, lithia, sodium citrate, and natural lime and lemon flavoring. Beneath this list, the capitalized slogan read: YOU LIKE IT / IT LIKES YOU.

After research conducted by John Cade in the 1940s and Morgen Schou in the 1950s, the drug was approved by the FDA - the U.S. Food and Drug Administration - in 1970 to treat manic-depressive illness, now known as bipolar disorder, though the Romans Soranus of Ephesus and Galen, in the 1st and 2nd centuries, called it mania, a condition for which they prescribed baths in alkaline waters, speculated to be rich in lithium.

Today, lithium is considered the “gold standard” for bipolar disorder, despite having caused some cases of poisoning, a problem resolved through dosage adjustments. Still, patients are advised to undergo regular tests to monitor its concentration in the blood and assess kidney function. Some who have undergone long-term successful treatment have suffered kidney damage. I came across two testimonies from people who experienced this. Strangely enough, neither regretted taking lithium; what they regretted was no longer being able to. The thing is, lithium drinks a lot of water.

Jujuy is a province in northwestern Argentina. On the morning of June 20, 2023, behind closed doors and in a lightning-fast process, a constitutional reform was ratified. The reform included, among other changes to the electoral system, the elevation of “social peace” to the status of a right, effectively criminalizing protests such as road and street blockades. It also introduced mechanisms to facilitate the dispossession of Indigenous lands and the disregard of ILO Convention No. 169, which, among other provisions, establishes that Indigenous peoples must be consulted regarding any measures that may affect them and must have the right to choose (and the right to choose not) when it comes to development projects on their lands. In 1989, Argentina, like Brazil, ratified the Convention.

The batteries that power electronic devices such as the computer on which this text was written, our cell phones, tablets, smartwatches, various health monitoring devices, photovoltaic solar energy systems, as well as drones and electric cars, not to mention all sorts of big and little machines and contraptions, are lithium-ion batteries. Thus, demand is exceedingly high. When I say “our”, I do not intend to blame anyone or stir up guilt. Rather, I seek to (re)activate memory in a non-moralistic way, to recall that we are all - often inescapably - implicated in infernal assemblages. Enthusiasts of these batteries defend them by arguing that they have high energy density, are lightweight, recyclable, have a low self-discharge rate, and boast a large and rapid recharge cycle; that they are efficient, require little maintenance, and - wonder of wonders - are “environmentally friendly” since they do not emit greenhouse gases.

Moreover, the cherry on top: thanks to cleaner processes with lower pollutant emissions, lithium extraction supposedly results in a smaller environmental impact on Earth compared to other energy storage technologies

The industry’s enthusiasm is so great that today lithium is referred to as “white gold” or “white oil.” Currently, the largest producers are Australia and Chile, accounting for 77% of global production, followed by China (13%), Argentina (6%), and, in fifth place with 1% of production, Brazil - or, more precisely, Minas Gerais.

Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina form what has come to be known as the “Lithium Triangle,” which holds about 60% of the world’s identified reserves. In lithium extraction from brines - the most commonly used method in salt flats - deep wells are drilled to reach lithium-rich brines, which are then pumped to the surface. The brine is channeled into vast evaporation ponds, where sunlight and wind accelerate evaporation. Once most of the water has evaporated, the remaining residues undergo purification to separate lithium from other elements. This procedure consumes enormous amounts of groundwater, depleting aquifers, disrupting aquatic ecosystems, and often leading to the salinization of freshwater sources, restricting access to water for both human and more-than-human communities. As if that were not enough, this method requires extensive land use, displacing ecosystems and human activities.

And, to top it off with a sour cherry, there is always the risk of contamination from the chemicals used in brine processing and lithium purification.

The communities resisting lithium mining in Salinas Grandes and the Puna of Jujuy — including Kolla and Atacama (Lickan Antay) peoples — have long defended their lands not only against extractivism but also in accordance with a way of being that acknowledges the presence and agency of more-than-human entities like Pachamama and ojitos de agua. There, Convention 169 has never been regulated, and one of the primary forms of protest is blocking streets and highways. In 2023, hundreds were injured.

After a police attack, a woman cried: “We are fighting to keep existing!”. As I've learned from Pérez, Pautasso and Pazzarelli, resisting to keep existing requires an embodied understanding of Permiso and Respeto, not just ethical imperatives, but ways of inhabiting a world where existence is always negotiated.

To ask permission is to recognize that the land, the water, and the spirits are not inert resources but beings with their own will, who do not merely react but respond. They can be pleased or offended, they can grant or withhold, they can aid or harm. To show respect is to listen, to acknowledge that one’s voice is but one among countless others in the cosmos. There is no guarantee because no being, human or otherwise, can claim absolute control over life’s unfolding; the relationships that sustain the world are contingent, reciprocal, and never fully determined in advance. This contrasts sharply with the state’s understanding of autonomy, which demands guarantees and does not accept the uncertainty of a cosmos that exceeds its control. But for those who resist in the cerro, the puna, and the salar, autonomy is not about securing outcomes, but about maintaining the fragile, living balance between all beings that make existence possible.

Jujuy is known for its thermal waters - there are 400 (!). Tourism campaigns highlight not only their exuberance but also their supposed ability to beautify the skin and cure rheumatism. According to the constitutional reform, those without official land deeds could face swift eviction through expedited legal processes. As we know, this disproportionately affects Indigenous populations, who often face the greatest difficulty in proving ancestral ownership of their own land.

As land titles dissolve ancestral rights in Jujuy, so too does mining dissolve mountains. In May 2023, led by the Government of Minas Gerais and with the support of the Ministry of Mines and Energy, the Lithium Valley Brazil initiative was launched on Nasdaq, integrating the Jequitinhonha Valley into this vast global supply chain. Now part of it are Araçuaí, Capelinha, Coronel Murta, Itaobim, Iringa, Malacacheta, Medina, Minas Novas, Pedra Azul, and Virgem da Lapa - along with the state’s largest concentration of quilombola and Indigenous communities, more than 20, many of them without officially demarcated lands.

The project touts “green lithium” and clean technology, no doubt an attempt to fill with smoke the memory of crimes like Mariana and Brumadinho. The export of this green white gold began in July.

In Jequitinhonha, no community was consulted - Brazil and Argentina are in agreement about Convention 169. Here, mining is done in hard rock, and the largest active project is Grota do Cirilo, operated by Sigma Lithium, a Canadian company.

Quilombola associations and Indigenous peoples report infestations of bats whose caves have been disturbed, disoriented bees, water shortages, rising living costs, and spiritual imbalance.

The Pankararu people in the region, already traumatized by the loss of waterfalls - places of immense significance in their relationship with more-than-human beings - due to dam construction, now fear for the world that exceeds humanity. In October 2023, the leader Cleonice Pankararu took their concerns to the United Nations, denouncing the impacts of lithium extraction.

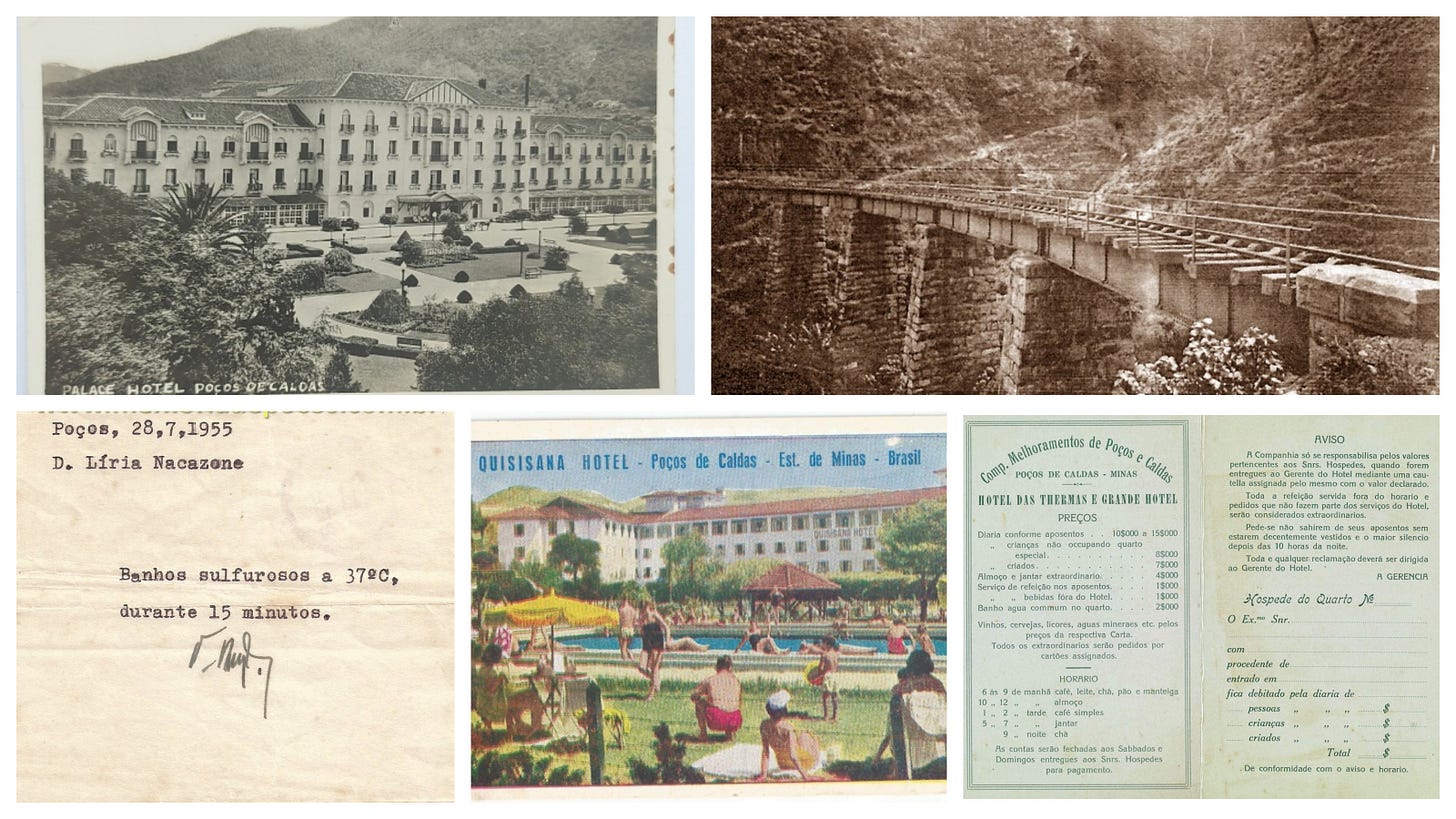

I could not help but think of José Miguel Wisnik’s beautiful book, Maquinação do mundo – Drummond e a mineração, in which the author discusses “the writer’s relationship with mining and, in particular, with the ‘mineral destiny’ of his hometown Itabira do Mato Dentro, a small colonial settlement embedded among immense iron ore deposits”:

The Pico do Cauê - whose specter the place compels us to envision through the trace of its spectral location - is no longer there, except as the hallucinatory presence of an absence. Exploited by Companhia Vale do Rio Doce, which was created specifically for this purpose in 1942, when Brazil entered World War II, and whose excavation intensified in the 1950s to serve the global steel market, the mountain, exceptionally rich in iron ore, was gnawed away by mining activity over the decades to the point of becoming an unnameable crater, carving its negative profile deep into the earth (2018).

I will let the poet speak for himself:

The Pulverized Mountain

I reach the balcony, see my mountain ridge,

the ridge of my father and my grandfather

of all the Andrades who have passed

and will pass, the mountain that does not pass.It was an Indians’ thing, and we seized it

to adorn and preside over life

in this saturnine valley where the wealth

most precious is its sight and contemplation.From afar it shows us a stern profile.

At every turn of the path it suggests

a form of being, in iron, eternal,

and breathes eternity into the current.This morning I wake and

do not find it.

Crushed into billions of shards

Sliding down the conveyor belt

clogging 150 wagons

in the monster-train of 5 locomotives

- the grandest train in the world, take note -

flees my mountain, goes

leaving on my body and in the landscape

a meager dust of iron, and this does not pass.

As for now, everyday we wake up and find less and less of the mountain, the ridge, the forest, the salt flat or the waterfall. How many Picos do Cauê?

I also could not help but recall a startling statement by Paul B. Preciado. It has never left my mind, and I cite the entire paragraph here for context.

I would like to propose that, from now on, we equivocate body and land.

When can a body be said to exist? What counts as a body? Can a body be someone's property? What if it is someone's property but the owner and the supposed body's subject do not coincide? What kind of politicai subjugation is this? Is a body made of flesh and bones? But then what are flesh and bones made of? And what if a body is made of signs, images, and sounds: Who can be accounted as the owner of these? Can those signs, those images, those sounds be mine even if my body isn't? Can they exist even if my body doesn't? Can existence be reduced to property? On the contrary, if existence is everything that exceeds property, when can a body be said to exist? What does it mean to inhabit a desacralized body? A profane body? A body opened to research as the mines of Potosí were once opened to extractivism? (2017: 120).

Let no one expect me to criticize Preciado for mentioning Potosí in the past when so many mines still suffer today. What haunts me is the idea of a body opened like a mine. Or rather, the relationship between body and mine.

Certain images, thoughts, or images when they enter thought, have immense persistence. Years later, during the COVID-19 quarantine, Preciado wrote an essay comparing pre-modern and contemporary disease management, considering “our” case. He called his mobile phone - whose battery is certainly lithium-ion - a cyber-companion animal, a cyborg in the service of surveillance.

That reactive and amiable cybernetic organ is the child of the Market and the Military-Industrial Complex, a creature born in the factories of technopatriarchal capitalism, fed directly with the rare materials extracted from the mines of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The heart of the Congo has been opened, ravaged, and from its depths, the nutrients have been extracted that transform a simple phone into a techno-living organ. Just as a baby is nourished by milk, the digital baby has been fed with tungsten, tin, tantalum, lithium, cobalt, nickel, arsenic, mercury... They say the digital orthosis is made of 'blood minerals' because to obtain the components that animate it, a dose of human blood has been required. The neoliberal patient feels that the same blood, the same crime, runs through their veins and through the microchips of their phone. They feel a new kind of disgusting electronic fraternity. For the first time, they feel inorganically alive. And organically dead. The neoliberal patient, like their phone, has emerged from the shattered womb of Africa. They live by devouring all other beings on the planet. They are Africavore, South Americavore, Indiavore, Chinavore... They have consumed everything, and now everything they have swallowed explodes in their colonial little white brain (2022: 227-228).

Being a Brazilian Latina, I can't have a colonial little white brain, but I do take lithium every day. I could not have written this text if I did not. This is not something one says lightly, but something confessed; not because people care about the traditional human and more-than-human communities in Jujuy, Araçuaí, or Itinga, where Sigma Lithium and the Companhia Brasileira de Lítio - companies that almost certainly supply lithium to Brazil’s pharmaceutical industry - operate. It is difficult because the person who does so is immediately perceived as mad; unbalanced; unpredictable.

When I started taking lithium, which truly changed my life, my doctor, out of caution, advised me to be careful about disclosing this information due to the stigma associated with it. “Especially in the workplace.” By writing-confessing-going-mad now, I feel my body being laid open like a mine. I feel my entrails exposed and pulsating, earth and flesh, a mine whose life we, mononaturalists of faith, might suddenly see.

I once read online, already drowning in lithiums and valleys, the testimony of a woman from the so-called Global North who, after discovering the supply chain of lithium carbonate, stopped taking it for “ethical reasons.” I am glad she was able to make that decision, relieving her conscience with the belief that she had let go of the devil’s hand.

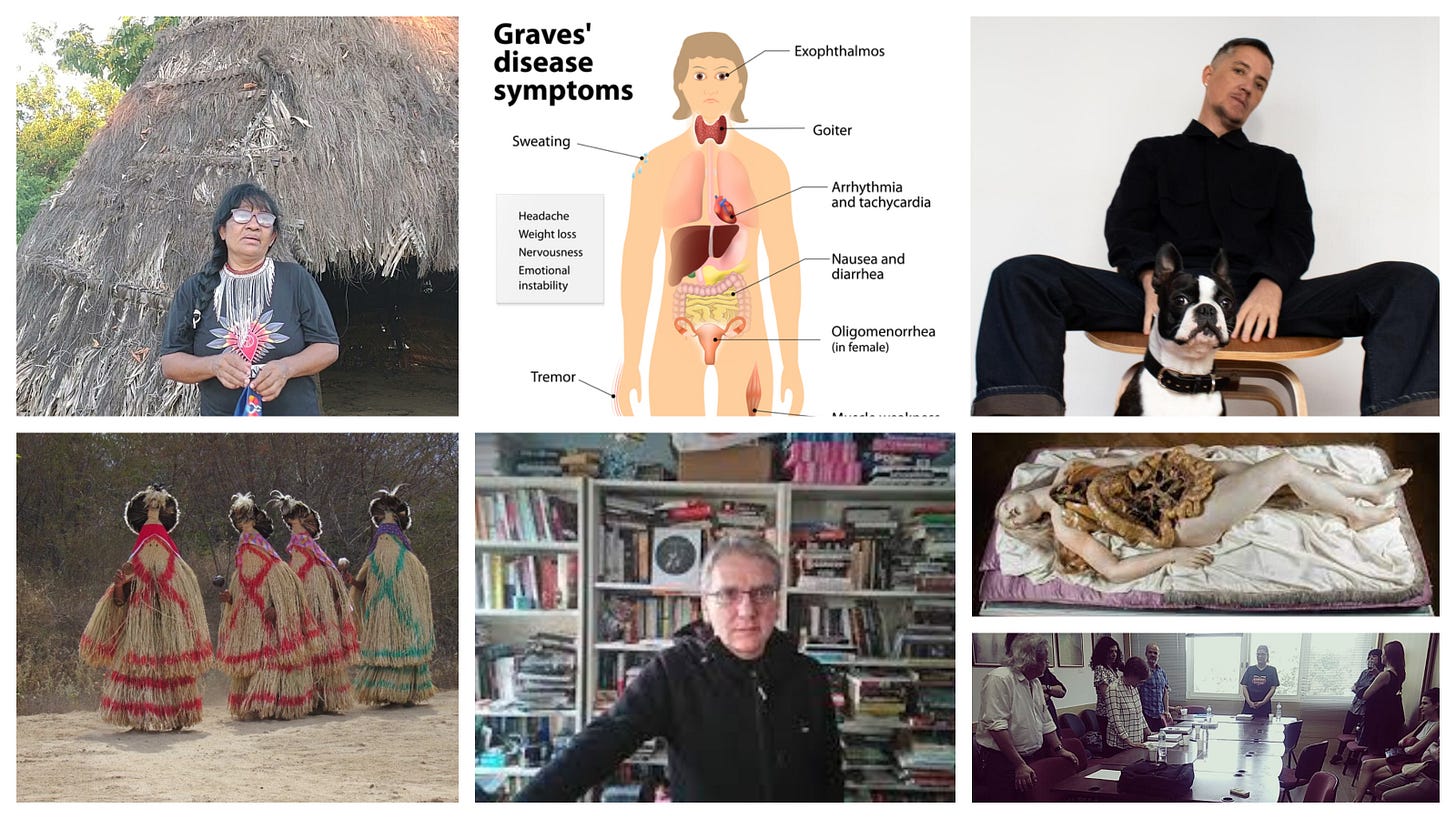

I will not commit the rudeness of listing my medical records, but I have a type of hyperthyroidism called Graves’ disease. When I was diagnosed in 2017 - the same year Preciado compared bodies to mines, the same year I earned my doctorate, the same year philosopher Mark Fisher, who suffered from major depression, took his own life - I researched extensively the origins of the substances I would need to take. I desperately wanted, and still want, to know with whom and in what ways I am connected. I was unable to find any information. Out of sheer luck, I discovered the origin of the lithium I take, as laboratories maintain these details as a matter of policy in strict secrecy.

I do not intend to stop taking lithium. There are many reasons, but I will state just one: because I want to want to be alive. I fully agree with Fisher that there is a visceral relationship between mental illness and capitalism. That is precisely why I do not give up medication.

In a 2005 post on k-punk, his blog, he wrote, with profound lucidity and bittersweet prophecy:

Ecological catastrophe and mental illness are present in capitalism's wrap-around simulation as warps, unassimilable discontinuities, that which cannot be but which, nevertheless, cannot be extirpated. Perhaps these negative Reals - these dark shadows which allow us to see kapital's striplit mall of the mind for what it actually is - have their complement in a positive Real, an event completely inconceivable in the current situation, but which will break in and re-define everything.

That which cannot be and yet cannot be eradicated: the destruction caused by lithium mines and the illness of those who come to need lithium.

For my part, I cannot stop thinking: am I devouring the Jequitinhonha Valley? In what place within this horrifying assemblage do I stand, and how do I participate in it? Did Deleuze dream of this infernal becoming?

This is not a becoming-animal in its various anti-institutional forms, nor a shamanic becoming-plant, nor even inebriation. This becoming-mineral in which I partake is not merely the conversion of one or multiple beings and ways of life into computer batteries or Elon Musk’s cars. Nor is it the idyllic transubstantiation captured by Michelangelo Frammartino in Le quattro volte (2010).

Speaking of cinema, when I watched Crimes of the Future (2022) by David Cronenberg, I pictured myself as one of the activists who ingest plastic bars, the residues that will persist into the future, worldwide.

In the movie, it was a political gesture. For me, it is vital. The leftover, the 1%, the mining detritus.

Unlike Drummond or the Pankararu, I do not feel connected to the land from which this mineral salt, this metal, was extracted. Although we are linked, this land and I, we have no bond. I do not dream of the Jequitinhonha Valley.

Nothing of it - its spirits, its struggles and fruits, its peoples and communities of all species, its beloved and desired territories - inhabits the pill. And yet, we are lashed together in a network: entire communities, devoured mountains, contaminated water, bodies saved and poisoned.

Could there be, as Fisher imagined, “a positive Real, an event completely inconceivable in the current situation, but which will break in and re-define everything?”

He also said that “all mental illnesses are neurologically instantiated, but this says nothing about their causation”, and that

The current ruling ontology rules out any possibility of a social causation of mental illness. The chemico-biologization of mental illness is of course strictly commensurate with its de-politicization. Considering mental illness an individual chemico-biological problem has enormous benefits for capitalism: first, it reinforces capital's drive towards atomistic individualization (you are sick because of your brain chemistry) and second, it provides an enormously lucrative market in which multinational 'psycho-mafias' can peddle their dodgy drugs (we can cure you with our SSRIs). It goes without saying that all mental illnesses are neurologically instantiated, but this says nothing about their causation. If it is true, for instance, that depression is constituted by low serotonin levels, what still needs to be explained is why particular individuals have low levels of serotonin. (2005).

I do agree with him, but also ask myself: wasn’t it precisely lithium carbonate that led me to the Jequitinhonha Valley and the salt flats of the Andean Altiplano?

What breaks forth is always unforeseen.

I do not feel intoxicated by lithium, but I experience almost-sensations and moments of presence. The land of Araçuaí and Itinga weighs in my stomach, the salinized water of Jujuy irritates my mouth, my throat.

There is a smell of brine that will not leave my nose, no matter how much I blow it.

One of lithium’s side effects is excessive thirst. It is recommended that patients drink plenty of water while taking this medication to protect kidney function.

I am always thirsty.

I drink a lot of water. I take; I do not give.

My body is an open mine that gives nothing.

* * *

Post-Scriptum: In 2024, I stopped taking lithium. Not because I was cured, but because of another diagnosis. Psychiatry, like mining, excavates through labeling. Bodies, like land, remain territories to be exploited.

There is no individual cure for a collective ailment. Perhaps the answer lies in the gesture of the women of Jujuy who know ecologies are always of minds. My survival now includes mapping the routes of the lithium that kept me - and keeps so many others - alive and joining those who block its passage.

What if every lithium prescription came with a reparations tax to fund Indigenous land defenders? What if lithium users funded Indigenous land defenders? What if “patient advocacy” meant fighting for the land that keeps us alive? What are we waiting for?

Magnificent!